An earlier version of this article did not mention that “time warrants” are, like all city and county debt, subject to the requirements of the Texas Constitution, Article 11, Sections 7(a) and 5(a), as applicable. Please consult your city attorney and/or bond counsel prior to the issuance of any time warrant to determine the most appropriate way to satisfy these and other relevant requirements.

As the COVID-19 pandemic drives economic life to a halt across Texas, the small business communities of cities and towns across the State are in crisis.

On average, companies with fewer than 500 employees have less than a month of cash reserves to cover their operating expenses. Smaller “Main Street” businesses – the restaurants, coffee shops, bars, groceries, hotels, auto repair shops, dry cleaners, and hair salons for which so many people work, and which contribute so much to local communities – often have just a couple of weeks’ worth of cash to keep running. This means that absent prompt financial assistance to help these businesses cover operating expenses during the ongoing shutdown, towns and cities across Texas could soon find themselves losing the core businesses on which their local economies and communities depend.

Unfortunately, the current assistance available to small businesses – primarily SBA “economic injury” loans – takes weeks to obtain and requires business owners to go through a complicated application process whose outcome is uncertain. Although the coronavirus relief bill taking shape in Congress will provide additional assistance in the form of business-interruption loans, those loans won’t be operationalized and small businesses won’t start seeing liquidity from them until at least 1-2 months from now — and possibly longer. Meanwhile, small businesses are facing the prospect of closure, and workers are experiencing layoffs and hour reductions.

Texas local governments can step in to bridge the present gap in assistance to small businesses affected by COVID-19 while building financially stronger, better networked, and more resilient communities poised for growth after the pandemic is controlled. Counties and municipalities can shift their use of well-known economic‑development authorities from the present focus on recruiting out-of-town industry to support homegrown businesses. They can use local procurement powers to make purchases of deferred‑performance goods and services from local businesses in exchange for long-term “time warrants”, which a business can factor or sell to obtain immediate funds. And they can use innovative legal strategies to organize local stakeholders around a community investment vision and raise capital for local businesses by blending governmental, private, and civic resources in public‑purpose funds.

Using these tools, Texas local governments can begin assembling economic stabilization networks that, on a day-to-day basis, can ascertain the damage being experienced by local businesses, organize local capital pools, and deploy them toward infusions of capital fit to the purpose of helping small businesses weather this public health and economic crisis.

Grants and Loans Under Chapters 380/381

Chapters 380 and 381 of the Texas Local Government Code are the most flexible instruments for economic development available to Texas municipalities and counties, respectively. They authorize local governments to establish programs to promote economic development, including, without limitation, programs making loans and grants of public funds, personnel, facilities, property and equipment to private parties, with or without charge. Moreover, a local government may “accept contributions, gifts, or other resources” from private or philanthropic groups to be used in a Chapter 380/381 program. Although cities and counties have typically used Chapter 380/381 authority to incentivize major corporations and industries to stay in, or move to, their jurisdiction, supporting small businesses in maintaining their operations and employees is just as squarely within the scope of that authority.

To exercise Chapter 380/381 authority, a city or county must take the following steps:

- Develop Chapter 380/381 Program(s). Each grant or loan under Chapters 380/381 must be made pursuant to a “program” that specifies at least the following matters:

-

- the “public purpose” that will be accomplished by providing the grant or loan (for example, development and diversification of the economy and the elimination of unemployment or underemployment in the local jurisdiction, with specific references to job creation and retention and the maintenance of business operations);

-

- the “demonstrable benefit” toward accomplishing the “public purpose” which the recipient will provide to the local government in exchange for the grant or loan (for example, the creation of a certain number of jobs, the retention of certain jobs that otherwise would be terminated, or continued operations in the jurisdiction for a stated period);

-

- effective methods for measuring and determining whether the recipient of the grant or loan has met its obligations (for example, inspection, audit, or other contract and management controls); and

-

- provisions for recapturing the grant or loan provided if the business does not meet its obligations.

- Adopt Chapter 380/381 Program(s). To satisfy the “program” requirement, the governing body of the municipality or county may adopt either (i) a general program governing the selection of all (or a group of) Chapter 380/381 recipients, as embodied in a comprehensive policy; or (ii) a separate program for each grant or loan arrangement with a recipient, as embodied in the economic development agreement with that recipient approved by the governing body. In either case, governing bodies should ensure that the resolution adopting the Chapter 380/381 program expressly makes fact- and locality-specific findings that (a) the public purpose of economic development will be accomplished through the program; (b) there will be a demonstrable benefit to the local government from the use of Chapter 380/381 incentives; and (c) sufficient safeguards are in place to determine whether a recipient has met its obligations and if the obligations have not been met, to recapture the incentives.

- Develop and Approve a Chapter 380/381 Agreement. A chapter 380/381 grant or loan must be governed by a written agreement approved via resolution adopted by the governing body of the applicable local government. Although no specific contract terms or conditions are statutorily required, a city may (and typically does) include: (i) provisions conditioning the incentive upon the recipient’s achievement of performance standards such as job creation, job retention, continued operations for a stated period, sales tax generation, or added tax base; (ii) provisions for the recapture of the incentive, typically through significant liquidated damages, if the recipient breaches the agreement; (iii) inspection, audit, certification, and other management controls; (iv) authority for the local government to terminate the agreement if the recipient fails to comply with the agreement; (v) references to Chapter 380/381 and the Texas Constitution Article VIII, Section 52-a; and (v) the method and structure of the grant or loan.

The flexibility of Chapters 380 and 381 makes them ideal instruments for stabilizing small businesses in crisis. Local governments can freely tailor grants and loans of public funds under these provisions to the specific financial circumstance with which the government and the business are contending. Simultaneously, local governments can extend their internal resources of personnel and property to satisfy some of the “wraparound” needs of small businesses, for things like professional services, maintenance equipment, or raw material. Finally, local governments can recruit private and philanthropic capital into their efforts by providing for the solicitation and administration of donations as part of their Chapter 380/381 programs. Through this combination, local governments can assemble community resources and deliver fit-to-purpose assistance to small businesses.

Strategic Public Procurement Using Time Warrants

A local government seeking to conserve cash reserves and avoid grants or loans of available funds may still help local businesses access liquidity through targeted public procurement using “time warrants”, which the business can sell or factor in exchange for cash. Time warrants are debt instruments like Certificates of Obligations, Tax Notes, and General Obligation Bonds, but they are easier to issue, more flexible to use, and can be paid over an extended maturity term. Specifically, time warrants (i) can be issued directly to any vendor in exchange for any personal property or labor; (ii) do not mature prior to the calendar year subsequent to their issuance and may have maturity terms as long as 40 years in the issuer’s discretion; and (iii) provided certain conditions are met, require neither a public notice period, nor an election, nor the approval of the Texas Attorney General. (That being said, a time warrant is a debt instrument subject to the requirements of Article XI, Sections 5(a) and 7(a), for the issuance of city and county debt. Please consult your city attorney and bond counsel to determine the most appropriate way to satisfy those requirements prior to the issuance of any time warrant.)

A time warrant is defined by state statute as “any warrant issued by a [municipality or county] that is not payable from current funds.”[1] For counties, “current funds” means “funds in the county treasury that are available in the current tax year, revenue that may be anticipated with reasonable certainty to come into the county treasury during the current tax year, and emergency funds.”[2] For municipalities, “current funds” means “money in the treasury, taxes in the process of being collected in the current tax year, and all other revenue that may be anticipated with reasonable certainty in the current tax year.”[3] The issuance of time warrants is wholly exempted from the requirement of Texas Attorney General’s approval for public securities.

For municipalities, the issuance of time warrants requires only the authorization of the municipality’s governing body, without a public notice period or an election, if the following conditions are satisfied: (a) the value of the contract being paid via time warrant(s) is less than $50,000 in municipal funds; and (b) the total value of time warrants issued by the municipality in the calendar year falls below certain thresholds — $7,500 if the city’s population is 5,000 or less; $10,000, if the city’s population is 5,001 to 24,999; $25,000, if the city’s population is 25,001 to 49,999; and $100,000 if the city’s population is more than 50,000. If the foregoing condition “(a)” is not met, the municipality must procure the contract to be paid with time warrants via a competitive bidding process under Chapter 252 of the Local Government Code, to be held following a two-week public notice period. By contrast, if the foregoing condition “(b)” is not met, the municipality will be required to hold an election to approve the time warrant issuance upon receipt of a petition signed by at least 10 percent of qualified voters in the municipality.

For counties, the issuance of time warrants requires only the authorization of the county’s governing body, without a public notice period, if the value of the contract being paid via time warrant(s) is less than $50,000 in county funds. However, a county is always required to hold an election to approve a time warrant issuance upon receipt of a petition signed by at least 5 percent of qualified voters in the county.

Once issued, a time warrant must be delivered directly to a vendor as payment for personal property or labor. Although the issuer cannot sell a time warrant for cash, the recipient vendor may sell the time warrant to any bank, factor, or other purchasers to obtain immediate funds. To facilitate the vendor’s ability to obtain liquidity for the time warrant, the issuing municipality or county should arrange for local banks to purchase the time warrant from the vendor.

Although time warrants are seldom used today, historically local governments used to fund many purchases through time warrants issued to vendors. It’s time to bring them back. The relative ease of their issuance and their flexibility makes them a suitable vehicle for local governments seeking to spread the cost of supporting small businesses in this crisis over time.

Raising Capital Using a Public-Purpose Fund

In recent years, cities across the Midwest — Cleveland with its Evergreen Cooperative Initiative, Cincinnati with its Center City Development Corporation, Philadelphia with its Kensington Corridor Trust, and Erie, PA, with its Erie Downtown Development Corporation, among others — have pursued innovative legal strategies to blend public, private, and civic capital into investment vehicles directed toward achieving public purposes while generating a return. Operating to align the previously siloed capital of diverse stakeholders, these “public-purpose funds” have multiplied the financial resources available to support neighborhood investment in their cities. In the present crisis, such public-purpose funds provide a useful vehicle through which Texas cities and counties can organize their own local institutions — banks, universities, businesses, investors, philanthropies, and neighborhood organizations — for a whole‑of‑community effort to deliver equity capital to hard-hit small businesses. Once the crisis subsidies, such public-purpose funds can become platforms for continued coordination and action by local stakeholders to achieve community goals.

Chapters 380 and 381 provide municipalities and counties with the requisite authority to facilitate the creation of a public-purpose fund in Texas. Although the constitutional prohibition on Texas local governments owning equity in private entities prevents them from directly sponsoring or participating in a typical private equity fund, municipalities and counties may, pursuant to a Chapter 380/381 program and related agreements, seed a private equity fund with loans or grants, take “first loss” positions to incentivize private investment in the fund, accept distributions from the fund or its manager, and impose related accountability and performance requirements. The flexibility of Chapter 380/381 authority means local governments have wide discretion to customize their financial, control, and oversight relationships with public-purpose funds.

To demonstrate its authority to lend or grant resources to a public-purpose fund, a local government should adopt a resolution or ordinance establishing a Chapter 380/381 program specifically for its relationship with the fund. The resolution should include at least the following:

- Public Purpose Statement. A statement that the public purpose of the program is to “promote local economic development and stimulate business and commercial activity in the [municipality or county]” in accordance with Chapter 380/381 through, for example and without limitation, seeding private equity funds dedicated to developing and diversifying the local economy, eliminating unemployment or underemployment, supporting growth and innovation in agriculture, and expanding local transportation and commerce; supporting organizations dedicated to coordinating economic development efforts among commercial, civic, and philanthropic institutions in the local community; and incentivizing private equity investment in (and the development of private equity capital pools for) local economic development and business and commercial activity, with emphasis on private equity investment by local commercial, civic, and philanthropic institutions.

[spacer height=”20px”] - Fact Findings. Findings to support the public purpose statement can include: (1) the depressed availability of debt and equity financing for local business and commercial activity during the present COVID-19 crisis; (2) the present rate of equity and debt flow into the census tracts within the jurisdiction; (3) the availability of siloed capital in local commercial, civic, and philanthropic institutions that could be incentivized into investment in local economic development; (4) the designation of census tracts within the jurisdiction as Opportunity Zones, State Enterprise Zones, or qualified low-income communities for the purposes of the New Markets Tax Credits; and/or (5) examples from other jurisdictions demonstrating the efficacy of public seed funding in catalyzing the development of multi-source private equity capital pools dedicated to public purposes.

- Demonstrable Benefit Statement. A statement of the demonstrable benefits the local government will demand or expects to receive in exchange for the incentives it provides under the Chapter 380/381 program can include: (1) direct job creation by the fund; (2) specific activities or milestones related to coordinating the economic development efforts of local stakeholders and the development of a community investment vision shared among the stakeholders; (3) specific activities or milestones related to the raising of stakeholder and other capital for the fund; (4) specific activities or milestones related to investing the fund’s capital in local economic development, including investment in local commercial or retail businesses, real estate projects, or industrial projects; and (5) distributions of surplus revenue from the manager of the fund to the local government (as described below), among others.

- Description of Recapture Mechanism. A description of the mechanism by which the local government will monitor incentive recipient performance and recapture the incentives provided if the fund fails to deliver the demonstrable benefits anticipated.

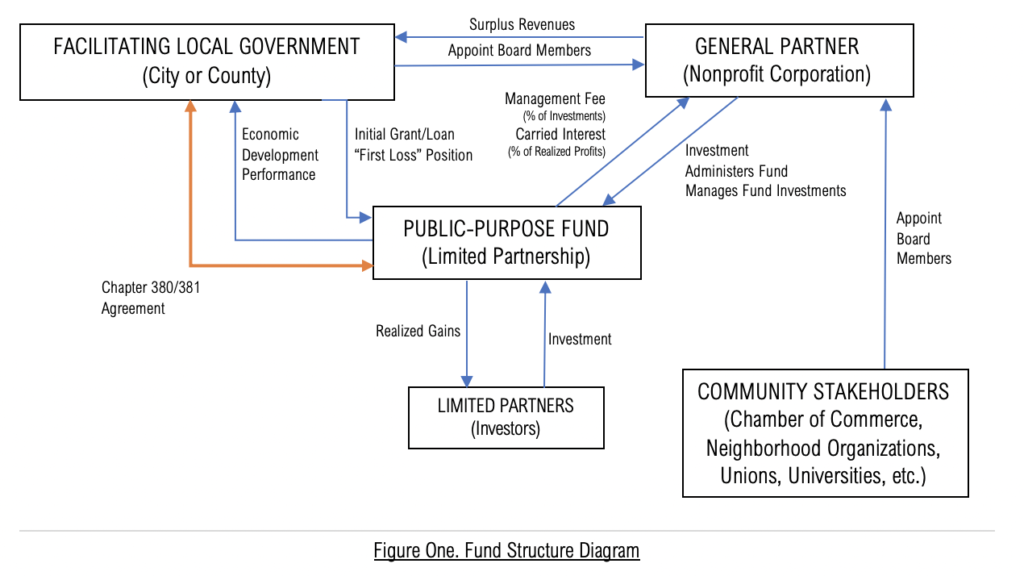

Like any private equity fund, a public-purpose fund should be formed as a limited partnership (the “Fund”). The general partner should be a nonprofit corporation (the “General Partner”) and should possess broad authority to invest in, administer, and manage investments for the fund. The limited partners should function as passive investors. The role of the facilitating local government should be limited to providing seed financing in the form of a Chapter 380/381 grant or loan, ensuring compliance with the Chapter 380/381 agreement, and, as described below, appointing directors to the General Partner’s board.

In this structure, at least three vehicles exist for holding the General Partner accountable to local stakeholders and the public purposes of the Fund: (i) the organizational documents of the General Partner; (ii) the organizational documents of the Fund; and (iv) the Chapter 380/381 agreement between the Fund and the facilitating local government. The certificate of formation and bylaws of the General Partner should, at a minimum, clearly state the nonprofit corporation’s purpose to advance economic development and require that all or a substantial portion of its directors be appointed by the facilitating local government and local stakeholders. The certificate of formation and partnership agreement of the Fund should require, and make explicit the right of, the General Partner to manage the Fund in a manner that balances the investors’ pecuniary interests, the best interests of the persons materially affected by the Fund’s activities, and the public purposes specified in the Chapter 380/381 agreement. Finally, in exchange for a loan or grant of public funds, the Chapter 380/381 agreement should include enforceable performance standards and entitle the local government to recapture public funds in the event that the General Partner is removed or material changes are adopted in the organizational documents of the General Partner or the Fund.

Aside from the normal economic considerations involved in fund formation, a local government establishing public-purpose funds should consider (1) whether to grant or loan its Chapter 380/381 funds; and (2) whether to require distributions of surplus revenue from the General Partner (which would only be meaningful if the General Partner actually took a management fee and carried interest from the Fund).

With respect to Chapter 380/381 funds, a loan would allow the local government to receive a return on its contribution to the Fund and, given the priority of debt over equity, preclude the local government’s funds from serving as “first loss” capital to incentivize private investment in the Fund. A grant would flip the tables: the local government would not receive a return on its grant contribution, but the granted funds would function as “first loss” capital for the Fund.

With respect to surplus revenue distributions, provisions may be included in the General Partner’s organizational documents requiring distributions of its surplus revenue (that is, revenue from management fees and carried interest exceeding operating expenses) to the facilitating local government. Alternatively, the General Partner’s board may authorize such distributions on an ad hoc basis from time to time. The extent to which the General Partner can command market-level fees for its management of the Fund will determine whether surplus revenue can be expected to materialize in sufficient quantities to warrant prospective arrangements in the General Partner’s organizational documents.

Conclusion

Local government response to the ongoing crisis is imperative. To survive and recover from the COVID-19 shock, small businesses – the heart and soul of our communities – need to replace lost income as fast and as efficiently as possible. Federal programs may work for some small businesses but, even considering the forthcoming stimulus bill, are likely to be slower and less flexible than many small businesses need. In this context, local governments must move urgently to organize local stakeholders around a whole-of-community effort to get fit-to-purpose capital to small businesses that need it. We hope the legal strategies described in this article can facilitate their efforts.

[1] See TEX. LOC. GOV’T. CODE § 252.001(8) (defining “time warrants” for municipalities); TEX LOC. GOV’T. CODE § 262.022(9) (defining “time warrants” for counties).

[2] See TEX LOC. GOV’T. CODE § 262.022(3) (defining “current funds” for counties).

[3] See TEX. LOC. GOV’T. CODE § 252.001(3) (Defining “current funds” for municipalities).